The Trauma Symptom of Amnesia: "I don't remember my childhood"

Amnesia and Trauma: Why It Happens

Amnesia can be a confusing and distressing experience for people living with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). It often shows up in those who dissociated during abuse, meaning their minds disconnected from what was happening as self-preservation. This can result in people being unable to remember traumatic events, or even large parts of their childhood.

What Is “Normal” Childhood Amnesia?

Everyone experiences “childhood amnesia,” where most memories before age three are forgotten.

Typically:

- Positive visual memories start around age 3½

- Verbal memories begin after age 4

- Negative memories are stored later

However, for those who experienced sexual, physical, or emotional abuse, memories often begin much later. People may also forget specific memories that occur after the standard childhood amnesia window. When a client says, “I can’t remember much from my childhood,” this can be a sign of trauma.

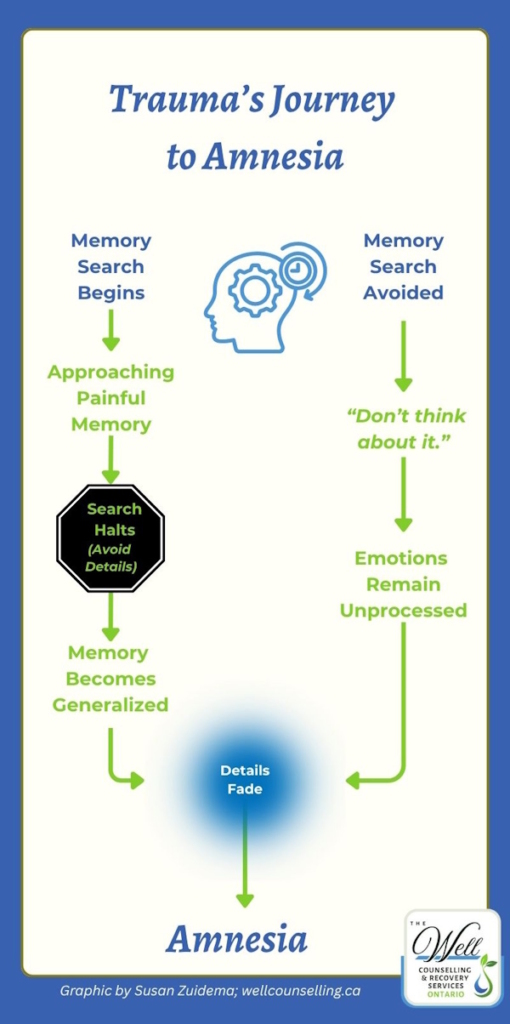

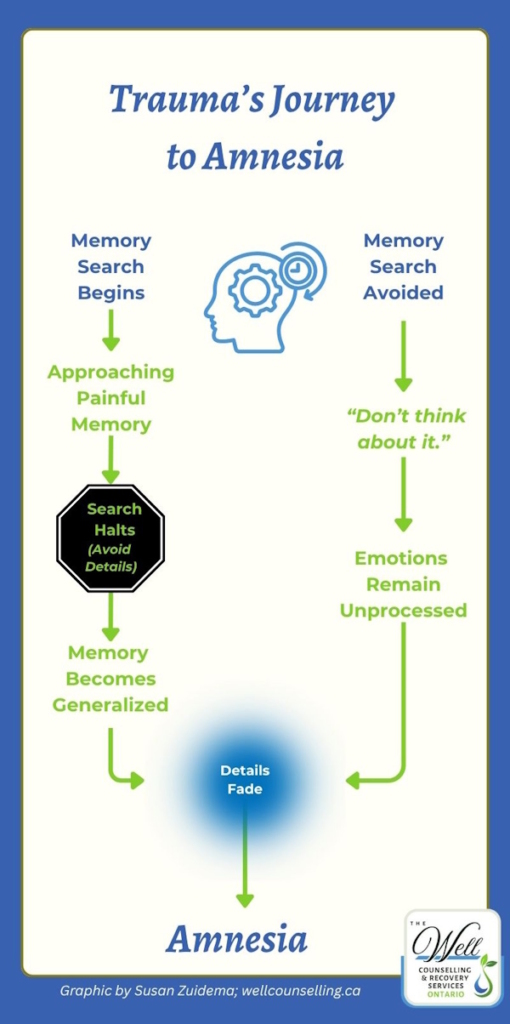

How Trauma-Related Amnesia Forms

Trauma-related amnesia often develops from avoiding painful memories.

The brain normally retrieves memories from broad → specific. But when it nears something traumatic, it may halt the search to avoid emotional pain, causing detailed memories to fade.

Actively trying not to think about something can also block emotional processing and lead to memory loss. Sexual trauma is most likely to trigger amnesia, followed by emotional and physical trauma[ii] [iii].

The Role of Betrayal in Memory Loss

Trauma-related amnesia often develops from avoiding painful memories.

The brain normally retrieves memories from broad → specific. But when it nears something traumatic, it may halt the search to avoid emotional pain, causing detailed memories to fade.

Actively trying not to think about something can also block emotional processing and lead to memory loss. Sexual trauma is most likely to trigger amnesia, followed by emotional and physical trauma[ii] [iii].

The experience of betrayal during traumatic abuse can also result in the development of amnesia. If the abuser is the child’s father, betrayal is automatically high, and amnesia is three times as likely. That’s because the child depends on their abuser for nurture and support so their brain may block out the abuse and hold onto more supportive moments. This allows the child to continue to interact quite normally with their abuser.[iv]

When Disclosure Is Met With Silence or Blame

A “double betrayal” occurs when a child discloses abuse to a trusted adult and receives a negative or dismissive response. This dramatically increases the risk of amnesia.[v]

However, when a child receives emotional support and the abuse is stopped, memory loss is much less likely. In that particular study, none of the children who received a helpful response later developed amnesia.[vi]

- Only 25% of children disclosed during the abuse

- More than half were not believed

- 50% developed amnesia afterward

However, when abuse stops and a child is supported emotionally, memory loss is far less likely—none of the supported children in the study later experienced amnesia.

Dissociation and Memory Loss

Dissociation is a specific way the brain handles trauma, and it can lead to a type of memory loss called dissociative amnesia. This means a person can’t remember key parts of a traumatic event, or sometimes entire time periods, or even who they are.[vii] Children may describe their memories as vague pieces rather than as full stories.

Can Trauma Memories Return?

There is no guarantee that people with trauma-induced amnesia will regain their memories, but memories can return. Common triggers include: [viii]

- flashbacks or nightmares

- things heard or read

- trauma reminders

- therapy

- images or visual cues

- sexual contact

- someone recounting the event

- major life experiences such as childbirth

Healing Trauma-Related Amnesia with EFIT

Many people come to therapy because they sense that something is missing or feel disconnected from their past. Emotionally-Focused Individual Therapy (EFIT) offers a safe way to explore this.

EFIT helps clients access the primary emotions tied to trauma—grief, fear, shame—so these experiences can be fully felt, processed, and integrated. This happens within a safe, attuned therapeutic relationship. The therapist monitors pace and intensity so the work remains manageable, grounded, and supportive.

If You’re Missing Pieces of Your Childhood

If you have large gaps in memory and want a safe space to explore them, we’re here to help.

Endnotes

[i] R. Joseph, “Emotional Trauma and Childhood Amnesia,” Consciousness & Emotion 4, no. 2 (2003): 151–79, https://doi.org/10.1075/ce.4.2.02jos.

[ii] Sabine Schonfeld et al., “Overgeneral Memory and Suppression of Trauma Memories in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder,” Psychology Press, Memory, 15, no. 3 (2007): 341, https://doi.org/10.1080/09658210701256571.

[iii] Colin A. Ross et al., “Reversal of Amnesia for Trauma in a Sample of Psychiatric Inpatients with Dissociative Identity Disorder and Dissociative Disorder Not Otherwise Specified,” Journal of Child Sexual Abuse 31, no. 5 (2022): 556, https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2022.2067096.

[iv] Nadia M. Wagner, “Sexual Revictimization: Double Betrayal and the Risk Associated with Dissociative Amnesia,” Journal of Child Sexual Abuse 22 (2013): 883, https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2013.830666.

[v] Wagner, 882.

[vi] Wagner, 882, 889, 897.

[vii] APA, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), 5th ed. (Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association, 2013), 291.

[viii] Ross et al., “Reversal of Amnesia for Trauma in a Sample of Psychiatric Inpatients with Dissociative Identity Disorder and Dissociative Disorder Not Otherwise Specified,” 555–56.